The Conde Lucanor is a classic text in medieval literature in the Castilian language, written by Don Juan Manuel in the early 14th century. It’s a book of exempla, or moral examples to guide one’s conduct and assist in one's general education. It also has a section dedicated to proverbs, which will be the focus of today’s entry.

It’s worth noting that proverb 6 is not really a proverb in itself, but rather another exemplum thrown into the mix, and consequently has not been numbered. The numeration presented here is editorial, with the idea being to aid readability. There are also footnotes explaining the vocabulary. The work is still a great source of interesting medieval exempla, and some great proverbs.

Segunda parte del Libro del Conde Lucanor et de Patronio

Razonamiento que faze don Juan por amor de don Jaime, señor de Xérica

Traducción del Señor Don Richard Pollard

|

D |

espués que yo, don Johán, fijo del muy noble infante don Manuel, adelantado mayor de la frontera et del regno de Murcia, ove acabado este libro del conde Lucanor et de Patronio que fabla de enxiemplos, et de la manera que avedes oído, segund paresce por el libro et por el prólogo, fizlo en la manera que entendí que sería más ligero de entender. Et esto fiz porque yo non só[1] muy letrado et queriendo que non dexassen de se aprovechar de'l los que non fuessen muy letrados, assí como yo, por mengua de lo seer, fiz las razones et enxiemplos que en el libro se contienen assaz llanas et declaradas.

Et porque don Jaime, señor de Xérica, que es uno de los omnes del mundo que yo más amo et por ventura non amo a otro tanto como a él, me dixo que querría que los mis libros fablassen más oscuro, et me rogó que si algund libro feziesse, que non fuesse tan declarado. Et só çierto que esto me dixo porque él es tan sotil et tan de buen entendimiento, que tiene por mengua de sabiduría fablar en las cosas muy llana et declaradamente.

Et lo que yo fiz fasta agora, fizlo por las razones que desuso he dicho, et agora que yo só tenudo de complir en esto et en al cuanto yo pudiesse su voluntad, fablaré en este libro en las cosas que yo entiendo que los omnes se pueden aprovechar para salvamiento de las almas et aprovechamiento de sus cuerpos et mantenimiento de sus onras et de sus estados. Et como quier que estas cosas non son muy sotiles en sí, assí como si yo fablasse de la sciençia de theologia, o metafisica, o filosofia natural, o aun moral, o otras sçiençias muy sotiles, tengo que me cae más, et es más aprovechoso segund el mio estado, fablar desta materia que de otra arte o sciençia. Et porque estas cosas de que yo cuido fablar non son en sí muy sotiles, diré yo, con la merçed de Dios, lo que dixiere por palabras que los que fueran de tan buen entendimiento como don Jaime, que las entiendan muy bien, et los que non las entendieren non pongan la culpa a mi, ca yo non lo queria fazer sinon como fiz los otros libros, más pónganla a don Jaime, que me lo fizo assí fazer, et a ellos, porque lo non pueden o non quieren entender.

Et pues el prólogo es acabado en que se entiende la razón porque este libro cuido componer en esta guisa, daqui adelante començaré la manera del libro; et Dios por la su merçed et piadat quiera que sea a su serviçio et a pro de los que lo leyeren et lo oyeren, et guarde a mí[2] de dezir cosa de que sea reprehendido. Et bien cuido que el que leyere este libro et los otros que yo fiz, que pocas cosas puedan acaesçer para las vidas et las faziendas de los omnes, que non fallen algo en ellos, ca yo non quis' poner en este libro nada de lo que es puesto en los otros, mas qui de todos fiziere un libro, fallarlo ha ý más complido.

Et la manera del libro es que Patronio fabla con el Conde Lucanor segund adelante veredes.

Razonamiento que faze Patronio al conde de muy buenos proverbios

Señor conde Lucanor —dixo Patronio—, yo vos fablé fasta agora lo más declaradamente que yo pude, et porque sé que lo queredes, fablarvos he daqui adelante essa misma manera, mas non por essa manera que en el otro libro ante deste.

Et pues el otro es acabado, este libro comiença assí:

I: En las cosas que ha muchas sentençias[3], non se puede dar regla general.

II: El más complido de los omnes es el que cognosce la verdat et la guarda.

III: De mal seso es el que dexa et pierde lo que dura et non ha preçio, por lo que non puede aver término a la su poca durada[4].

IV: Non es de buen seso el que cuida entender por su entendimiento lo que es sobre todo entendimiento.

V: De mal seso es el que cuida que contesçerá a él lo que non contesçió a otri[5]; de peor seso es si esto cuida porque non se guarda.

[Breve enseñanza]

¡O Dios, señor criador et complido!, ¡cómo me marabillo porque pusiestes vuestra semejança en omne nesçio, ca cuando fabla, yerra, cuando calla, muestra su mengua; cuando es rico, es orgulloso, cuando pobre, non lo preçia nada; si obra, non fará obra de recabdo; si esta de vagar, pierde lo que ha; es sobervio sobre el que ha poder, et vénçesse por el que más puede; es ligero de forçar et malo de rogar; conbídase de grado, conbida mal et tarde; demanda quequier [6]et con porfía; da tarde et amidos[7] et con façerio[8]; non se verguença por sus yerros, et aborreçe quil' castiga; el su falago es enojoso; la su saña, con denuesto; es sospechoso et de mala poridat; espantasse sin razón; toma esfuerço ó[9] non deve; do cuida fazer plazer, faze pesar; es flaco en los vienes et reçio en los males: non se castiga por cosa quel' digan contra su voluntad; en grave día nasçió[10] quien oyó el su castigo; si lo aconpañan non lo gradesçe et fázelos lazdrar[11]; nunca conçierta en dicho nin en fecho, nin yerra en lo quel' non cumple; lo quel dize non se entiende, nin entiende lo quel' dizen; siempre anda desabenido[12] de su compaña; non se mesura en sus plazeres, nin cata su mantenençia; non quiere perdonar et quiere quel' perdonen; es escarnidor, et él es el escarnido; querría engañar si lo sopiesse fazer; de todo lo que se pagaría[13] tiene que es lo mejor, aunque lo non sea; querría folgar et que lazdrassen los otros. ¿qué diré más? En los fechos et en los dichos, en todo yerra; et lo demás, en su vista paresçe que es nesçio, et muchos son nescios que non lo parescen, mas el que lo paresçe nunca yerra de lo seer.

VI: Todas las cosas an fin et duran poco et se mantienen con grand trabajo et se dexan con grand dolor et non finca[14] otra cosa para sienpre sinon lo que se faze solamente por amor de Dios[15].

VII: Non es cuerdo el que solamente sabe ganar el aver[16], más eslo[17] el que se sabe servir et onrar él del como deve.

VIII: Non es de buen seso el que se tiene por pagado[18] de dar o dezir buenos sesos[19], mas eslo el que los dize et los faze.

IX: En las cosas de poca fuerça, cumplen las apuestas palabras; en las cosas de grand fuerça, cumplen los apuestos et provechosos fechos.

X: Más val al omne andar desnuyo[20] que cubierto de malas obras.

XI: Quien ha fijo de malas maneras et desvergonçado et non reçebidor de buen castigo, mucho le sería mejor nunca aver fijo.

XII: Mejor sería andar solo que mal acompañado.

XIII: Más valdría seer omne soltero, que casar con mujer porfiosa.

XIV: Non se ayunta el aver de tortiçería[21] et si se ayunta, non dura.

XV: Non es de[22] crer en fazienda agena el que en la suya pone mal recabdo.

XVI: Unas cosas pueden seer acerca et otras alueñe pues dévese omne atener a lo çierto.

XVII: Por rebato et por pereza yerra omne muchas cosas; pues de grand seso es el que se sabe guardar de amas.

XVIII: Sabio es el que sabe sofrir et guardar su estado en el tiempo que es turbio.

XIX: En grant cuita et periglo bive qui reçela[23] que sus consejeros querrían más su pro que la suya.

XX: Quien sembra sin tiempo non se marabille de non seer buena la cogida.

XXI: Todas las cosas paresçen bien et son buenas, et paresçen mal et son malas, et paresçen bien et son malas, et paresçen mal et son buenas.

XXIII: Más val alongarse omne del señor tortiçiero que seer mucho su privado.

XXIV: Quien desengaña con verdadero amor, ama; quien lesonia, aborreçe.

XXV: El que más sigue la voluntat que la razón, trae el alma et el cuerpo en grand periglo.

XXVI: Usar más de razón el deleite de la carne, mata el alma et destruye la fama et enflaqueçe el cuerpo et mengua el seso et las buenas maneras.

XXVII: Todas las cosas yazen so la mesura; et la manera es el peso.

XXVIII: Quien non ha amigos sinon por lo que les da, poco le durarán.

XXIX: Aborreçida cosa es qui quiere estar solo, et más quien quiere estar con malas compañas.

XXXI: Como quier que contesçe, grave cosa es seer dessemejante a su linage.

XXXII: Cual omne es, con tales se aconpaña.

XXXIII: Más vale seso que ventura, que riqueza, nin linage.

XXXIV: Cuidan que el seso et el esfuerço que son dessemejantes, et ellos son una cosa.

XXXV: Mejor es perder faziendo derecho, que ganar por fazer tuerto; ca el derecho ayuda al derecho.

XXXVI: Non deve omne fiar en la ventura, ca múdanse los tiempos et contiénense las venturas[24].

XXXVII: Por riqueza, nin pobreza, nin buena andança, nin contraria, non deve omne pararse del amor de Dios.

XXXVIII: Más daño recibe omne del estorvador que provecho del quel' ayuda.

XXXIX: Non es sabio quien se puede desenbargar[25] de su enemigo et lo aluenga.

XL: Qui a sí mismo non endereça[26], non podría endereçar a otri.

XLI: El señor muy falaguero es despreciado; el bravo, aborrecido; el cuerdo, guárdalo con la regla.

XLII: Quien por poco aprovechamiento aventura grand cosa non es de muy buen seso.

XLIII: ¡Cómo es aventurado qui sabe sofrir los espantos et non se quexa para fazer su daño[27]!

XLIV: Si puede omne dezir o fazer su pro[28], fágalo, et sinon, guárdes[s]e de dezir o fazer su daño.

XLV: Omildat con razón es alabada.

XLVI: Cuanto es mayor el subimiento, tanto es peor la caída[29].

XLVII: Paresçe la vondat del señor en cuales obras faze et cuales leyes pone.

XLVIII: Por dexar el señor al pueblo lo que deve aver dellos, les tomara lo que non deve.

XLIX: Qui non faz buenas obras a los que las an mester, non le ayudarán cuando los ovier[30] mester.

L: Más val sofrir fanbre que tragar bocado dañoso.

LI: De los viles se sirve omne por premia; de los buenos et onrados, con amor et buenas obras.

LII: Ay verdat buena, et ay verdat mala.

LIII: Tanto enpeeçe[31] a vegadas[32] la mala palabra como la mala obra.

LIV: Non se escusa de ser menguado qui por otri faze su mengua.

LV: Qui ama más de cuanto deve, por amor será desamado.

LVI: La mayor desconosçençia[33] es quien non conosçe a sí; pues ¿cómo conozcrá[34] a otri?

LVII: El que es sabio sabe ganar perdiendo, et sabe perder ganando.

LVIII: El que sabe, sabe que non sabe; el que non sabe, cuida que sabe[35].

LIX: La escalera del galardón es el pensamiento, et los escalones son las obras.

LX: Quien non cata las fines fará los comienços errados.

LXI: Qui quiere acabar lo que desea, desee lo que puede acabar.

LXII: Cuando se non puede fazer lo que omne quiere, quiera lo que se pueda fazer.

LXIII: El cuerdo sufre al loco, et non sufre el loco al cuerdo, ante[36] le faz premia.

LXIV: El rey rey reina; el rey non rey non reina, más es reinado.

LXV: Muchos nombran a Dios et fablan en El, et pocos andan por las sus carreras.

LXVI: Espantosa cosa es enseñar el mudo, guiar el çiego, saltar el contrecho; más lo es dezir buenas palabras et fazer malas obras.

LXVII: El que usa[37] parar lazos en que cayan los omnes, páralos a otri et él caerá en ellos.

LXVIII: Despreçiado deve seer el castigamiento del que non bive vida alabada.

LXIX: ¡Cuantos nombran la verdat et non andan por sus carreras!

LXX: Venturado et de buen seso es el que fizo caer a su contrario en el foyo que fiziera para en que él cayesse.

LXXI: Quien quiere que su casa esté firme, guarde los çimientos, los pilares et el techo.

LXXII: Usar la verdat, seer fiel, et non fablar en lo que non aprovecha, faz llegar a omne a grand estado.

LXXIII: El mejor pedaço que ha en el omne es el coraçon; esse mismo es el peor.

LXXIV: Qui non esseña et castiga sus fijos ante del tiempo de la desobediençia, para siempre ha dellos pecado.

LXXV: La mejor cosa que omne puede escoger para este mundo es la paz sin mengua et sin verguença.

LXXVI: Del fablar biene mucho bien; del fablar biene mucho mal.

LXXVII: Del callar biene mucho bien; del callar biene mucho mal.

LXXVIII: El seso et la mesura et la razón departen et judgan las cosas.

LXXIX: ¡Como sería cuerdo qui sabe que ha de andar grand camino et passar fuerte puerto si aliviasse la carga et amuchiguasse[38] la vianda!

LXXX: Cuando el rey es de buen seso et de buen consejo et sabio [et] sin maliçia, es bien del pueblo; et el contrario.

LXXXI: Qui por cobdiçia de aver dexa los non fieles en desobediençia de Dios, non es tuerto de seer su despagado[39].

LXXXII: Al que Dios da vençimiento de su enemigo guárdesse de lo porque fue vençido.

LXXXIII: Si el fecho faz grand fecho et buen fecho et bien fecho, non es grand fecho. El fecho es fecho cuando el fecho faze el fecho; es grand fecho et bien fecho si el non fecho faz grand fecho et bien fecho.

LXXXIV: Por naturales[40] et vatalla campal[41] se destruyen et se conquieren[42] los grandes regnos.

LXXXV: Guiamiento[43] de la nave, vençimiento de lid, melezinamiento de enfermo, senbramiento de cualquier semiente, ayuntamiento de novios, non se pueden fazer sin seso de omne et voluntat et gracia speçial de Dios.

LXXXVI: Non será omne alabado de complida fialdat fata que todos sus enemigos fíen del sus cuerpos et sus fechos. Pues cate[44] omne por cuál es tenido si sus amigos non osan fiar de'l.

LXXXVII: Qui escoge morada en tierra do non es el señor derechudero[45] et fiel et apremiador et físico sabidor et complimiento[46] de agua, mete a sí et a su compaña en grant aventura[47].

LXXXVIII: Todo omne es bueno, más non para todas las cosas.

LXXXIX: Dios guarde a omne de fazer fecho malo, ca por lo encobrir abrá de fazer otro o muchos malos fechos.

XC: Qui faze jurar al que bee[48] que quiere mentir, ha parte en el pecado.

XCI: El que faze buenas obras a los buenos et a los malos, recibe bien de los buenos et es guardado de los malos.

XCII: Por omillarse al rey et obedeçer a los principes, et honrar a los mayores et fazer bien a los menores, et consejarse con los sus leales, será omne seguro et non se arrepintrá[49].

XCIII: Qui escarnece de la lisión[50] o mal que biene por obra de Dios, non es seguro de non acaesçer a él.

XCIV: Non deve omne alongar el bien, pues lo piensa, porque non le estorve la voluntat.

XCV: Feo es ayunar con la voca sola et pecar con todo el cuerpo.

XCVI: Ante se deven escoger los amigos que omne mucho fie nin se aventure por ellos.

XCVII: Del que te alaba más de cuanto es verdat, non te assegures de te denostar más de cuanto es verdat.

(al inglés)

The second part of the book of Count Lucanor and Patronius

The argument which Don Juan makes with his esteem for Don Jaime, Lord of Xérica

Don Juan, son of the most noble prince Don Manuel, after having crossed most of the frontier of the kingdom of Murcia, and having completed this book Count Lucanor and Patronius, which treats of exempla, and the manner in which you heard them as they figure in the book itself and in the prologue, carried this out in a way which I understood to be less burdensome to understand. And I did this because I am not very well read, and I wanted those who were not well read to be able to make use of them, thus I, for a want of being so, arranged the arguments and exempla which are to be found in the book in a very plain and clear manner.

And as Don Jaime, Lord of Xérica, (who is, of all people, the one whom I most esteem and it is possible that I esteem no one else as I do him), told me that he wished my books to read more arcanely, and he beseeched me to pen a book that wasn’t so simple to fathom. And I am certain that he told me this because he is a most subtle man and of such great intelligence, who possesses, to a fault, wisdom in speaking in matters of a manner most plain and clear.

And what I have done up to this point, I have done for the aforementioned reasons, and now that I am responsible for carrying them out, as much as I could according to your wishes, I will treat in this book of the things of which I understand people may make use of, for the saviour of their souls and for the bettering of their bodies and the preservation of their honour and well-being. And although these subjects are not very subtle in and of themselves, additionally if I were to verse upon the science of theology or metaphysics, or natural or even moral philosophy, or upon the other subtlest sciences, I find it more natural and befitting to me, according to my own constitution, to treat upon this subject more than any other art or science. And since these matters which I resolve to speak upon are not in themselves greatly subtle, I shall say, that with God’s mercy, what I say with words, those who are of sound intellect like Don Jaime should understand them well, and those who do not, may they not place the blame on to myself, (for I did not wish to write like this, more to continue in the manner of the other books), but rather blame Don Jaime[51], who beseeched me to carry it out in this manner, or blame those who cannot and wish not to understand them.

And as the prologue is completed, in as much as the reason for why I wish to compose the book in this guise is understood, from here on in, I shall commence with the content of the book; and may God will it that it be of service to Him, and of benefit to those who read it and hear it, and may He ward me from saying anything that may be considered reprehensible. And well do I think that anyone who should read this book and the other ones which I have written, that there are few things that can happen in a man’s life and work that they should not find some use for them, for I did not wish to include in this book anything that has been published in others, but for those individuals who have written a book before, they should find this one to be more complete.

And the style of the book is one of Patronius speaking with Count Lucanor, as you shall see later on.

The explanation that Patronius gave to the Count of some very fine proverbs

“Lord Count Lucanor”, said Patronius. “I have up to now spoken to you in the most concise manner I was able to, and as I know that you have beseeched it, I shall speak to you from here on, in the very same manner, but not in the exact manner of the other book preceding this one”.

And with the other book now finished, this one begins thusly:

1. In matters, there exist many opinions; it is not possible to provide a general rule for them

2. The most perfect man is one who knows truth and keeps it.

3. Of ill mind is he who gives up on and lets go of what requires time and doesn’t pay, [preferring] that which can be completed in a short space of time.

4. Weak minded the man who believes that he understands through his own understanding, things which are above all of [general] understanding itself. Comment: (I.e., a man is ignorant for believing that what he knows is somehow more special than what other men know, or already knew).

5. Weak minded is he who believes that things will befall him that never happened to someone else.

[A succinct teaching regarding

the evil of man[52]]

Oh God, consummate Lord and creator! How you amaze me, for you placed Your likeness in every ignorant person, for when they speak, err or when they are quiet, they show their shortcomings; when it is a wealthy person, he is haughty, when poor, he values nothing; if he labours, he won’t carry it out with conviction; if he is prone to sloth, he loses everything he owns; he is contemptuous towards the man in power, and fickle towards the most able; he is quick to seek help, and dreadful at asking for it; he bequeaths at own his leisure, he bequeaths dreadfully and at the eleventh hour; he asks anyone for a favour, and obstinately; he gives at the eleventh hour, both reluctantly and with great pain; he is not ashamed of his errors, and abhors those who correct him; his flattery is bothersome; his spite invective; his is suspicious and untrustworthy; he becomes unnerved without cause; he seeks assistance where there is no need for it; when he means to be agreeable, he is burdensome; he is meagre in good deeds, and mighty in bad ones; he doesn’t rectify himself for anything that they say to him which goes against his wishes; accursed is the man who took heed of his counsel; if he is in company, he shows no gratitude towards them and causes hardship upon them; he is never true to his word or deed, failing to keep them both as a matter of course; whatever he says is unfathomed, nor does he fathom what is said to him; he is always found standing aloof from his cohort; he does not steady himself in his pleasures, nor does he take note of his own preservation; he wishes not to forgive, but wants to be forgiven; he is both the mocker the mocked; he would gladly deceive if he knew but how; in all that he would boast of, his way is the best, even if it weren’t the case; he would gladly take delight in himself and have others suffer.

What more shall I say? In both deeds and words, he errs in everything; and with others, to his mind he thinks one to be ignorant, for many are ignorant without looking it, yet the one who seems it never commits the error of being so.

6. All things have an end, and last but for a short time and are maintained through much labour, and are lost through great strife, and nothing remains forever, save that which is done but through the love of God.

10. ‘Tis better for a man to walk naked than to be covered in wicked deeds.

11. Whoever has a son who is of poor breeding, shameless and not receptive toward proper correction; it would have been much better for the man that he had never had a son.

12. Better to walk alone than to be in bad company.

13. It would be better to be a bachelor, than be married to an obstinate woman.

14. One cannot accumulate capital through wrongful means, and if that’s the case, that capital won’t last long.

15. You shouldn’t confide in someone in external affairs, when that person puts poor care toward their own affairs.

16. Some matters can be [considered] from close at hand, others from a distance, yet one must attend to what is true[53].

19. One lives in great distress and danger who suspects his advisers of looking after their own benefit more than his own.

20. He who sows at the wrong time shouldn’t be surprised at a bad harvest.

25. Whoever follows his own wishes more than reason, brings great danger upon his body and soul.

28. One who has friends only for what they give to him, won’t have them for very long.

29. It’s an abhorrent thing for someone to wish to be alone, and even worse for them to wish to be in bad company.

30. A man who wishes to govern his subjects by force and not through good deeds, will find that the hearts of his subjects will plead for someone [else] to govern them.

32. Tell me who your friends are, and I’ll tell you who you are.

33. Better a sound mind than fortune, wealth or lineage.

36. One must never place his faith in fortune, for times change and fortune ebbs.

38. Greater damage will a man receive from the one who hinders him, than gain from the one who helps him. I.e., Better to avoid people who hinder us than just asking for help out of those situations.

43. How fortunate is the man who knows how to suffer threats from others, and not gripe about exacting retribution!

46. The greater the ascent, the worse the fall.

(i.e., The bigger they are, the harder they fall).

51. One gives service to the vile by brute force; to the good and the honourable with love and good deeds.

52. There is truth that is good, there is truth that is bad.

53. Many times, a bad word caused as much harm as a wicked deed. (i.e., many a time a bad word broke one’s skull).

54. One is not exempt from dishonour, even when the dishonour is carried out in another man’s name.

61. One who wishes to finish what he desires, should desire something that he can finish.

66. It is a dreadful thing for a mute man to teach, a blind man to guide, a lame man to jump; even worse is to utter good words and commit foul deeds.

68. Disdain should be the punishment for one who doesn’t lead a blessed life.

69. How many mention Truth, yet don’t tread upon its paths!

70. Blessed and of sound mind the man who made his adversary fall into the very pit that he would have had him fall into.

72. To put truth to use, to be loyal, and to not speak in matters he has no experience in, make a man attain a great condition.

73. The greatest piece of man lies in his heart; the very same piece is also the worst.

75. The greatest thing that a person could wish for this world is a peace that is not wanting nor unabashed.

76. From speaking well comes much that is good; from speaking well comes much that is bad.

77. From keeping quiet comes much that is good; from keeping quiet comes much that is bad.

78. Sound mind, moderation and intellect both classify and judge things.

80. When a king is of sound mind and of good and sagacious counsel without malice, he is an asset for his people; and vice versa.

85. A ship’s guidance, victory in battle, medicine for the sick, the sowing of any given seed, the union of bride and groom; these cannot be realized without one’s acumen, and the will and special grace of God.

86. A man shall not be praised for absolute trustworthiness until all of his enemies place the wellbeing of their bodies and actions in him. For each man will be esteemed thusly, if his friends don’t venture to have trust in him.

94. One should not exaggerate his kind act, so that (all things considered) his goodwill not become complacent.

96. A man should sooner choose friends that he has great trust in, so that he not compromise himself for them.

97. With someone who praises you more than is the truth, don’t be surprised that they defame you more than is the truth.

[1] «só»: soy.

[2] Generalmente escrito sin el acento en la mayoría de las ediciones.

[3] «sentençias»: opiniones.

[4] «durada»: duración.

[5] «otri»: otro.

[6] «quequier»: pron. uno indeterminado, cualquiera.

[7] «amidos» (Del lat. invītus): adv. de mala gana o a la fuerza.

[8] «façerio» (Prob. der. del façerir, de faz y herir): pena.

[9] «ó» (Del lat. ubi): adv. en donde, donde.

[10] «en grave día nasçió»: nació en día malafortunado, en mal momento.

[11] «lazdrar» (De lacerar): padecer y sufrir trabajos y miserias.

[12] «desavenir»: desconcertar, desconvenir.

[13] «pagaría»: se jactaría.

[14] «finca»: queda. Cf. el port. fica.

[15] Nótense el uso de polisíndeton en las cuatro repeticiones de et.

[16] «aver»: dinero; victo.

[17] «eslo»: lo es.

[18] «pagado»: satisfecho, ufano.

[19] «sesos»: opiniones, dictámenes.

[20] «desnuyo»: desnudo.

[21] «tortiçería»: malicia, injusticia.

[22] «non es de»: no se debe.

[23] «reçela»: sospecha.

[24] «contiénense las venturas»: la suerte se reduce o se comprime.

[25] «desenbargar» (desembargar): quitar el impedimento, desembarazar.

[26] «endereçar»: encaminarse derechamente a un lugar o a una persona.

[27] «fazer su daño»: dañar, injuriar.

[28] «fazer su pro»: hacer algo beneficioso o provechoso.

[29] Posiblemente este proverbio tiene su origen en un poema de Claudio, En Rufinam, Lib. I, 22-24 [Contra Rufino]: «iam non ad culmina rerum iniustos crevisse queror; tolluntur in altum, ut lapsu graviore ruant». [Ya no quejo de que los injustos llegan hasta el culmen de las cosas [del éxito]; son llevados a lo alto, para ser lanzados con más fuerza en su caída].

[30] «ovier»: hubiere. Es el subjuntivo de futuro. Cf. el port. houver.

[31] «enpeeçer» (empecer): dañar.

[32] «a vegadas»: a veces. Cf. el cat. a/de vegades.

[33] «desconosçençia»: desconocimiento, ignorancia.

[34] « conozcrá»: conocerá.

[35] La comilla es editorial para facilitar la lectura. El refrán recuerda a Sócrates.

[36] «ante»: antes, más bien.

[37] «usa»: suele.

[38] «amuchiguar» (Del lat. vulg. *multificāre): multiplicar.

[39] «despagado»: enemigo, adversario.

[40] «natural»: vasallo de un rey.

[41] «batalla campal»: batalla general y decisiva entre dos ejércitos.

[42] «conquerir»: conquistar. Cf. el inglés, to conquer.

[43] «guiamiento»: acción y efecto de guiar.

[44] «cate» (Del lat. vulg. cata, y este del gr. κατά katá 'según', 'conforme a', 'cada', entre otros muchos significados.): forma antiguada de cada.

[45] «derechudero»: derechurero, exacto, legítimo o según derecho.

[46] «complimiento»: previsión, surtimiento.

[47] «aventura»: peligro.

[48] «bee»: ve.

[49] «arrepintrá»: arrepentirá.

[50] «lisión»: lesión.

[51] The self-defence employed by the author, and his placing the blame on to Don Jaime regarding potential criticisms, are borderline humorous.

[52] Not really a proverb in itself, so I have not numbered it. The accompanying title is editorial.

[53] I.e., Some matters can be blatantly clear, others obscured, yet one must always attend to what is true.

[54] «state»: condition or wellbeing.

[55] I.e., γνῶθι σεαυτόν, know thyself.

[56] I.e., Wise is the man who knows when not to give up, and to quit while he’s ahead.

[57] This phrase has as its orgin the latin refrain: «ipse se nihil scire id unum sciat». It is known as a “Socratic Paradox”.

[58] Refrains 61 and 62 utilize a chiasmus.

[59] Lit. “faithfuls” (leales) in the original.

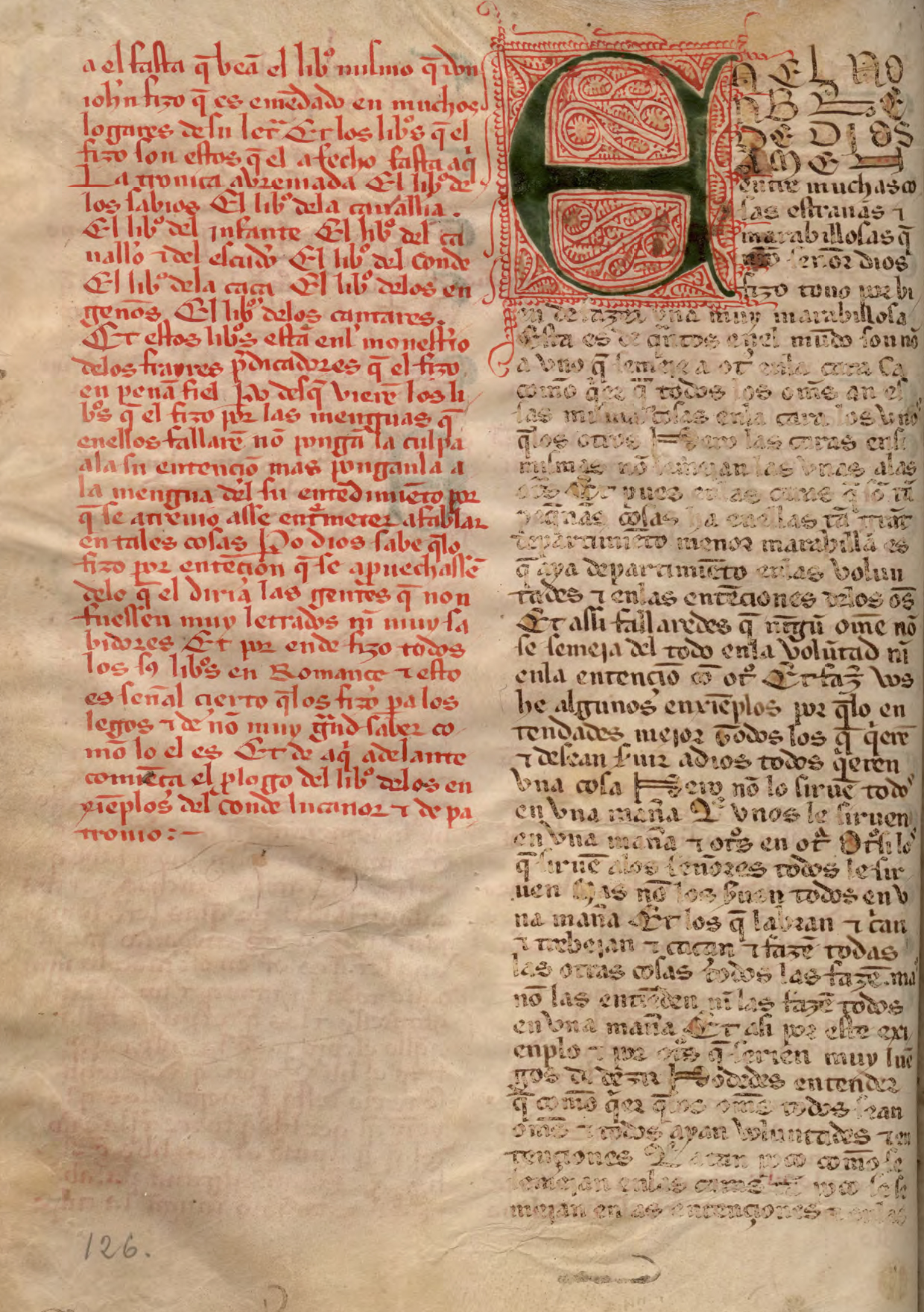

Galería:

A possible portrait of Don Juan Manuel,

from an altarpiece in Murcia Cathedral.