Proverbia Mundi IV: The moral proverbs of Sem Tob (Proverbios Morales)

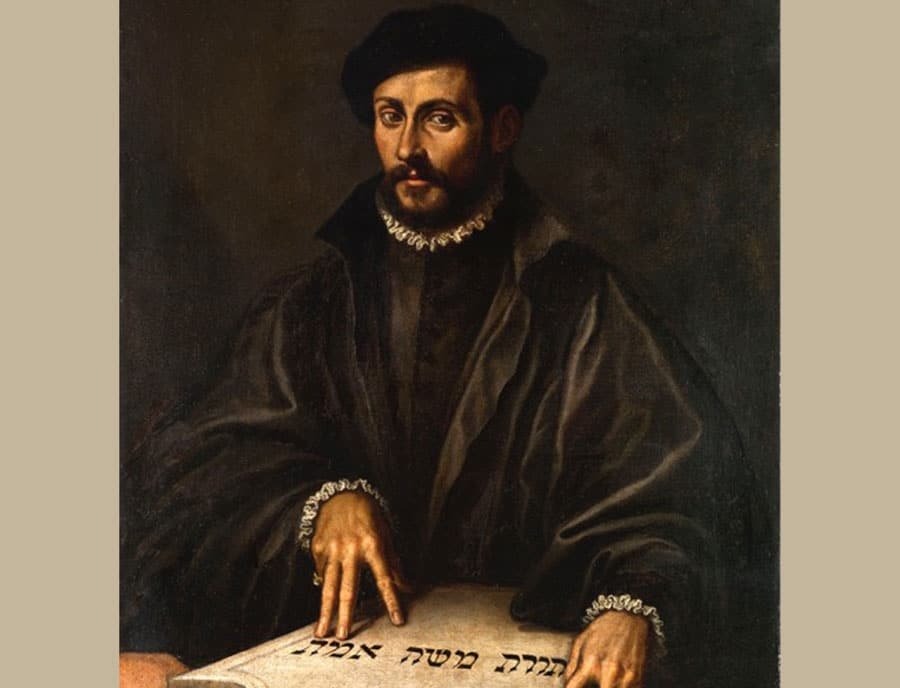

As a continuation of the last entry, we will visit another Ladino text from 14th century Spain. While not possessing the condensed magic of the Ladino refrains proper, these versified sayings were written by Sem Tob (full name Sem Tob ben Ishaq ibn Ardutiel; שם טוב בן יצחק אבן ארדוטיאל) in the middle of the 14th century. The original title given to these proverbs was «Consejos y documentos al rey don Pedro», [Counsels and documents destined for King Don Pedro], the title being a later addition by the 15th century politician and writer Marqués de Santillana.

Sem Tob’s work is noticeable influenced by the «Cuaderna vía» current of gnomic literature to come out of medieval Spain. As a literary genre, it is known as «Mester de clerecía» (Ministry of Clergy). Regarding the Spanish text, I have replaced j as a vowel with i, to aid readability. Constructions like «enel» have been separated as «en el», for the same reason. Each saying is numbered according to the standard order from the manuscript edition collected the CORDE, a Spanish language corpus database. As an added bonus, we have included a rimed verse translation, just to add some spice. This rounds off our tour of Sephardic sayings, I hope you got some enjoyment from them. See you next time!

I.

«por nasçer en espino[1], —non

val la rrosa çierto

menos nin el buen vjno —por salyr del sarmiento». [003]

Eng.

A rose born of the thorn is no less valid,

nor so is a fine wine born of the vine shoot.

Rimed version

It is a thing no less fine, a rose of ignoble root,

and much less so a good wine, though risen from the vine shoot.

and much less so a good wine, though risen from the vine shoot.

II.

«non vale el açor menos por salyr del mal nido

nin los enxenplos buenos por los dizer judío»[2]. [004]

Eng.

The goshawk is worth no less for

having hailed from a bad nest,

nor are praiseworthy examples, though

originating from Jewish culture.

Rimed version

The goshawk, no less a bird is he, though from a bad nest,

nor is the wise Jewish word, worth any less than the rest.

III.

«Commo la candela mesma, tal cosa es el omne

franco, que ella se quema por dar a otro lunbre». [76].

Eng.

Like the candle itself, such is the nature of a

blunt man; burning so as to give light to another.

Rimed version

A blunt man’s word leads to burn, like a candle in one’s hand,

giving light so one can learn, and

his own mind understand.

IV, V.

«Non puede omne[3] aver — en el mundo tal amjgo

commo el buen saber, —nin peor enemigo. [284].

«Que la su torpedat[4], —Que del torpe su saña

Más pesa en verdat —Que arena; e maña[5]», [285].

Eng.

One cannot have such a great friend in the world

as good knowledge; nor a worse enemy

as good knowledge; nor a worse enemy

Than own’s one barbarity, for a brutish man’s madness

truly weighs him down more than sand and a bundle of esparto.

Rimed version

What is one’s best acquaintance during our time on this earth,

is

without doubt sapience; nor

is there a greater dearth

in man, than his own daft crimes,

for the madness of his hand

often weighed him down at times, even more than wood or sand.

VI.

«Decir siempre verdat maguer que daño tenga,

et non la falsedad maguer pro della venga». [289].

Eng.

Speak the truth always, though it cause harm,

and not lies, though one should gain from it.

Rimed version

Always strive to speak the truth, even though it may cause pain.

Never speak a lie forsooth, though therein one may

find gain[6].

VII.

«Cosa que tanto cuenple para amigos ganar,

non ha como ser sienple e bien se rrazonar». [323].

Eng.

He possesses the quality to win over friends,

yet not the one for being simple and reasoning

well.

Rimed version

In the realm of the social, he can make many a friend,

but not in the logical, can he himself well defend.

VIII.

«No ha cosa más larga que lengua de mintroso,

nin çima más amarga a[7] comienço

sabroso». [350].

Eng.

There’s nothing longer than a liar’s tongue;

nor does a most bitter sprout taste sweet from the start.

Rimed version

there is nothing one can

tout longer than a liar’s tongue,

furthermore, a bitter sprout never tasted sweet when young.

IX.

«Non ha fuerte castillo más que la lealtad,

«Non ha fuerte castillo más que la lealtad,

nin

tan ancho portillo com la mala

verdat». [353].

Eng.

There’s no fortress stronger than loyalty,

nor passageway narrower than false truth.

Rimed version

There exists no edifice more solid than loyalty;

nor alley more venomous than to lack in honesty.

X.

El mundo la verdat de tres cosas mantyen:

juyzyo e verdat, e paz que dellos vyen. [359].

Eng.

The world is sustained by three things:

judgement, truth, and the peace that comes with

these first two.

Rimed version

All things in life are forsooth comprised of but these three things:

peace, judgment and of course truth; the

first two fly on its wings.

XI.

«E el juyzyo es la piedra çimental:

de todas estas tres, el es la que más val». [360].

Eng.

Good judgement is the building block:

of all these three [things], it has the most

worth.

Rimed version [6 syllables in this refrain]

and know that of these things it has been since time’s birth

and know that of these things it has been since time’s birth

judgement that most joy brings and which has the most worth.

XII.

«Nunca de una camisa amas non se vistieron,

Jamás de una devisa[8],

señores nunca fueron». [377].

Eng.

Never from one shirt did two ever dress

themselves;

Nor from a shared seigniory did two ever end up

as absolute lords.

Rimed version

By just one garment wearing, two men could never be dressed,

Nor by dominion sharing as

lords shall they be addressed.

XIII.

«Torna sin detenencia[9] la mar mansa muy brava,

e el mundo hoy desprecia al que ayer honraba»[10]. [382].

Eng.

A gentle sea turns turbulent without demurral,

and today’s world despises what it honoured

yesterday.

Rimed version

Like the way a tame sea runs without

a warning astray,

So too the world today shuns what

it honoured yesterday

XIV.

«El torpe bien andante, que con su gran

torpeza,

nol’ pasa por talante que puede aver pobreza». [406].

Eng.

The well-off dim-wit, who in his great

doltishness,

never entertained the thought that there could

be such a thing as poverty.

Rimed version

The very well-off dim-wit, through his own monstrosity,

not even the slightest bit, ever noticed poverty.

XV.

«Com el pez en el rrío, viçioso e rriyendu[11],

¡non sabe el sandio la red quel’ van teçiendo!». [409].

Eng.

Like a fish in a stream, lazy and smiling away,

the fool is unaware of the net they’re devising for him.

Rimed version

A fish swimming in a stream, without worries in this life,

A fish swimming in a stream, without worries in this life,

he is not able to glean that what awaits him is strife.

XVI.

«Quanto más cae de alto, tanto peor se fiere;

quanto más bien ha,

tantu más teme si’s perdiere». [415]

[I.e., cuanto más altos son, más dura la caída].

Eng.

The higher one falls from, the more damage is

done;

the more good things one possesses, the more one

fears losing it all.

Rimed version

With wealth, the greater the man, the

harder will be the fall;

the more hath he and his clan, more his fear losing it all.

[I.e, the bigger they are, the harder they

fall].

XVII.

«De una fabla conquista puede nascer e muerte;

e de una sola vista crescer grant amor fuerte».

[420].

[420].

Eng.

From one word can arise war and death;

and from just one gaze can a strong love be

forged.

Rimed version

Bad words can light life ablaze, strike

a deathblow from above;

and through just a single gaze, one may nurture a true love.

and through just a single gaze, one may nurture a true love.

XVIII.

«Pero lo que fablares, si en escrito non es,

si tú pro fallares, negarlo has después. [421].

Eng.

Yet that which you speak, if not in writing be,

and if you should find gain thereof, you’d best

deny it thereafter.

Rimed version

With regard to what you say, if it not be in writing,

and serves you in a great way, to deny is the right thing.

and serves you in a great way, to deny is the right thing.

XIX.

«Onça

de mejoría de lo espiritual[11]

conprar

no se podría con quanto el mundo val». [486].

Eng.

One ounce of spiritual improvement

could not be bought up with even the world’s

worth.

Rimed version

Not an ounce one could buy of progress for the spirit,

even though one may well try selling the world’s worth for it.

XX.

«En que come e beve semeja alimaña:

«En que come e beve semeja alimaña:

así muere e bive como bestia, sin falla. [494].

Eng.

With what he eats and drinks, he resembles an animal:

Thus, shall he live and die like a beast,

without exception.

Rimed version

In his style of drink and feast,

he lives like an animal;

And so shall he die a beast, in a

way most damnable.

XXI.

«En el entendimiento como el ángel es:

no ha despartimiento, si en cuerpo non

es». [495].

Eng.

In his wisdom he is as an angel:

yet not a difference will it make, if in body

he is not.

Rimed version

In his mind there is prudence, as if he were a seraph:

yet shall make no difference, if body

he cares not of.

XXII.

«mezura que levanta —

sympleza et cordura

et poder que quebranta —

sobervia et locura»

[605].

Eng.

A mixture which instils simplicity

and reason

and a power which defeats haughtiness and madness.

[I.e., desiderata for one to aspire to.

Imagine a tacit subject like “these qualities are to be desired:”].

Imagine a tacit subject like “these qualities are to be desired:”].

Rimed version

A mixture which can instil reason and simplicity,

and a power which can

kill smugness and insanity.

[1] «espino»: se entiende

mejor aquí como espina.

[2] Santillana’s

paraphrase reads thus: «No vale el açor menos / por nasçer en vil nído,/

ni los exemplos buenos /

por

los dezir judío». The fact that each final line contains 7 sílabas, it’s

probable that Santillana was correct in his reading of the saying. Also it is

possibe «dir», an medieval variant of «dezir» was the intention, but then the

verse would only have 6 syllables, instead of the expected 7.

[3] En

otras ediciones, figura como «otro».

[4] En otras ediciones

figura como «poridad», que no encajaría bien con el tema del refrán.

[5] «maña»: Manojo

pequeño, de lino, cáñamo, esparto.

[6] The 1st and 3rd verses of the

original only have 6 syllables (if «siempre» is not to be interpreted as

a diphthong, in which case it would have 7 syllables), rather than the expected

7. However, this is an exception, so I have kept to the standard 7 syllable

structure. It may even be a slip of the hand from the copyist. For example: «et

non dir la falsedad» (“and do not speak a falsehood”) would work, and

adds up nicely to 7 syllables. This is just my conjecture though.

[7] «a»: ha, eso es, tiene.

[8] «devisa» (Del lat. divīsa

'repartida'): Señorío solariego que se dividía entre hermanos coherederos

(DRAE).

[9] «detenencia»: detención.

[10] There is another versión which reads: «torna sin detenençia la mar muy buena brava / et el mundo

despreçia oy al que ayer honrrava»,

but the inclusión of oy [today] adds an extra syllable unnecessarily, which makes

this reading doubtful.

[11] «rriyendu»: riendo.

[12] Should probably be written «espiritüal», to indicate that the word has 5 syllables instead of 4, to add up to the desired 7.

[12] Should probably be written «espiritüal», to indicate that the word has 5 syllables instead of 4, to add up to the desired 7.