Returning

to Oviedo’s A Natural and General History

of the Indies, today’s entry focuses on a fishing technique recorded by

Oviedo, and written with some fine detail. The “Indians” (originally derived

from the Latin indigo, the colour indigo)

in question (if the paragraph is to be believed) are most likely Taínos, being the most prominent Caribbean culture

encountered by Colombus and his men. Like everything connected to him, it may be apocryphal and in fact he could just be referring to the Indonesian or Philippine Archipelago, the so-called "East Indies". Still, the description is vividly written, so I include it in the series.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, A General and Natural History of The Indies.

From chapter 8

[A Caribbean manner of fishing]

“I

want to mention here a manner of fishing that the Indians of Cuba and Jamaica use

at sea, and another manner of hunting and fishing technique that is also used

by the said Indians of these two islands when they hunt for wild geese; and it’s

in this manner: there is a fish the size of a palm, or a little bigger, that is

called remora, ugly to the eye, but of enormous sprit and cunning; of which it

frequently occurs that, among other types of fish, they are captured in nets,

(I have eaten many of these). And the Indians, when they wish to retain and

farm some of them, they keep them in seawater, wherein they feed them, and when

they wish to use one for fishing, they bring it to sea in their canoe or boat,

and place it here in the water, and tie it with a thin string, but taut, and

when they spot any large fish, like a tortoise [1]or

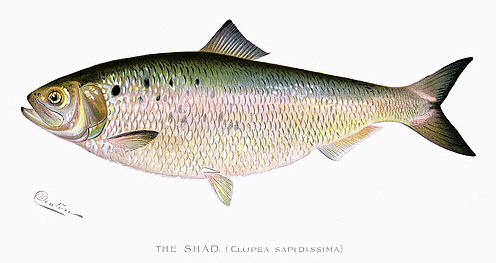

shad[2],

which exist out on those seas, or any other [creature] that it may be, which

happens to tread waters or in a way that it be visible, the Indian takes this

remora fish in his hand and praises it with other, saying to it in his own

tongue that it be in good spirits and have a strong heart and be diligent, and

other exhortative words [said] with vigour, and that it procure to be bold and

latch on to the largest and best fish that it should come by out there; and

when he deems it fit, he releases it and launches it towards where the fish

are, and said remora flies like an arrow, and latches hold of the side of the

tortoise, or its belly or wherever it is able to, and clings on to the tortoise

(or any other large fish, or any other [creature] that it wishes [to cling

to]). The which, as it feels itself being attacked by that small fish, in the

waters flees from one place to another, while the Indian does nothing but tug

and stretch the cord at every point, which measures several fathoms, and to the

end of it is tied a cork or stake, or something light as a marker that should

stay above water, and within a short while, the large fish or tortoise to which

the remora clings itself to, weary, approaches coastal land, and the Indian

begins to grab hold of the string in his canoe or boat, and when he has but a

few fathoms to go, begins to throw them [toward the shore], purposefully, pace

by pace, and throws them guiding the remora and the fish to which it’s clinging

on to, until they reach land, and as it is about 4 and a half to 9 square

metres [from land]; the very waves of the sea prompt it out [of the water],

and the Indian at the same time grabs hold of it and takes it out [from the

water] until he can get it dry; and when the hunted fish is then taken out of

water, with much care, pace by pace, he gives words of thanks to the remora

which carried out its task and worked and detaches it from the fish to which it

thusly clung on to, and was so greatly latched on to it, that if he tried to

separate the two with force, he would kill the said remora or break it in to

pieces”.

[1] Obviously

not a fish, rather a reptile of the order Testudinidae.

[2] Alosinae, part of the herring family Clupeidae.

[texto original]

«Quiero decir aquí una manera de

pescar que los indios de Cuba y Jamaica usan en la mar, y otra manera de caza y

pesquería que también en estas dos islas los dichos indios de ellas hacen

cuando cazan y pescan las ánsares bravas, y es de esta manera: hay unos

pescados tan grandes como un palmo, o algo más, que se llama pexe reverso[1],

feo al parecer, pero de grandísimo ánimo y entendimiento; el cual acaece que

algunas veces, entre otros pescados, los toman en redes (de los cuales yo he

comido muchos). E los indios, cuando quieren guardar y criar algunos de éstos,

tiénenlo en agua de la mar, y allí danle a comer, y cuando quieren pescar con

él, llévanle a la mar en su canoa o barca, y tiénenlo allí en agua, y átanle

una cuerda delgada, pero recia, y cuando ven algún pescado grande, así como

tortuga o sábalo, que los hay grandes en aquellas mares, u[2]

otro cualquier que sea, que acaece andar sobre aguados [3]o

de manera que se pueden ver, el indio toma en la mano este pescado reverso y

halágalo con la otra, diciéndole en su lengua que sea animoso y de buen corazón

y diligente, y otras palabras exhortatorias a esfuerzo, y que mire que sea

osado y aferre con el pescado mayor y mejor que allí viere; y cuando le parece,

le suelta y lanza hacia donde los pescados andan, y el dicho reverso va como

una saeta, y aferra por un costado con una tortuga, o en el vientre o donde

puede, y pégase con ella o con otro pescado grande, o con el que quiere. El

cual, como siente estar asido de aquel pequeño pescado, huye por la mar a una

parte y a otra, y en tanto [4]el

indio no hace sino dar y alargar la cuerda de todo punto, la cual es de muchas

brazas, y en el fin de ella va atado un corcho o un palo, o cosa ligera, por

señal y que esté sobre el agua, y en poco proceso de tiempo, el pescado o

tortuga grande con quien el dicho reverso se aferró, cansado, viene hacia la

costa de tierra, y el indio comienza a coger su cordel en su canoa o barca y

cuando tiene pocas brazas por coger, comienza a tirar con tiento poco a poco, y

tirar guiando el reverso y el pescado con quien está asido, hasta que se

lleguen a la tierra, y como está a medio estado [5]o

uno; las ondas mismas de la mar lo echan para fuera, y el indio asimismo le

aferra y saca hasta lo poner en seco; y cuando ya está fuera del agua el

pescado preso, con mucho tiento, poco a poco, y dando por muchas palabras las

gracias al reverso de lo que ha hecho y trabajado, lo despega del otro pescado

grande que así tomó, y viene tan apretado y fijo con él, que si con fuerza lo

despegase, lo rompería o despedazaría el dicho reverso».

-Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, Historia general y natural de las Indias

(1535-1557).

[1] «peje

reverso»: rémora.

[2] 1535: «o».

[3] «aguados»: entiéndase aguas.

[4] «en tanto»: entretanto.

[5] «estado»: 11. m. Medida de

superficie que tenía 49 pies cuadrados (DRAE).

Gallery:

a remora, certainly ugly to the eye

American shad

No comments:

Post a Comment